Lead authors: Vien Suerte-Cortez (ANSA-EAP) & Carolina Cornejo (ACIJ)

Contributing authors: Carolina Vaira , Hirut M'cleod, Manuel E. Contreras (World Bank)

- Module 03

- Essential concepts of collaboration

- Constructive Engagement

Constructive Engagement

Constructive engagement is the process of “building a mature relationship between two naturally opposable parties—i.e., citizens or citizen groups and government—bound together by a given reality.” (ANSA-EAP, 2013). That process involves building trust between the two parties; it is evidence based and is heavily driven by results and solutions (The Co-Intelligence Institute). Spaces for participation are created, wherein mutual trust and openness are required to facilitate meaningful and sustained dialogue and negotiation. In the context of SAI—citizen engagement, citizens and citizen groups are not outsiders. Rather, they sit at the same table and are given the same powers and responsibilities as those of state auditors.

When problems and gaps are identified during the implementation and delivery of government programs and services, it is the role of citizens and civil society to point out those problems and find ways to work with the government to solve them. That process is called collaborative problem solving. It is when citizens and the government deliberately sit together to identify possible interventions.

Once solutions have been identified for implementation, citizens and government must continuously communicate every step of the way. That communication ensures that each party is kept in the loop and is aware of the actions taken. The process of continuing dialogue is not always easy. Tensions arise when reform initiatives take place—a normal reaction given the different mandates and limitations of each institution. However, communication to resolve those tensions helps strengthen the relationship and trust between institutions. A dialogue transforms into a process of “shared exploration towards greater understanding, connection, or possibility (The Co-Intelligence Institute).” Throughout the process of continuing dialogue, we undergo the following stages: (1) enriching perspectives and achieving understanding, (2) framing choices and deliberating, (3) deciding; and (4) implementing (ANSA–EAP, 2010). These stages occur in one continuous loop to facilitate effective communication between and among the key actors in the reform process.

Guidelines for dialogue*

- 1. We talk about what's really important to us.

- 2. We really listen to each other.

- 3. We say what's true for us without making each other wrong.

- 4. We see what we can learn together by exploring things together.

- 5. We avoid monopolizing the conversation.

The process of building a mature relationship between SAIs (or any government agency) and citizens is characterized by the following:

- An attitude of trust building among the involved parties

- The use of evidence based on data generation and analysis to make claims;

- An orientation toward achieving concrete results or finding solutions

- A predisposition toward sustaining the engagement

The presence of those characteristics deepens the appreciation of the roles and responsibilities that government and civil society play when working toward reforms in governance.

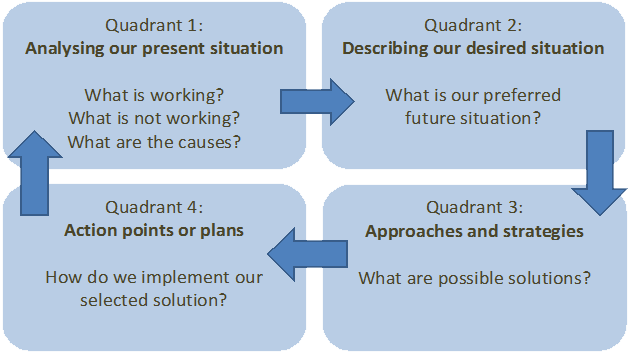

The Affiliated Network for Social Accountability in East Asia and the Pacific (ANSA–EAP) adapted and customized the World Bank’s Quadrant Solving Tool and used it during constructive engagement workshops. That tool provides a concrete approach to identifying and solving problems collaboratively and identifies the nature of engagement between social accountability actors.

In Quadrant 1, accomplishments and issues are identified based on the present situation. Situation and stakeholders’ analysis tools can also be used for this quadrant. Trigger questions in this quadrant focus on the following:

- What is working, and what do we want to continue doing?

- What do we want to change or improve?

- What is not working, and what do we want to stop?

Assessing the relationship between and among the key actors is also important at this point. The quality of relationships usually dictates the type of negotiation strategy that must be taken into account. One may use the quadrant below for reference:

Quadrant 2 describes the desired future state. The ideas generated from this quadrant may be linked and organized using a concept map or a mind map. A concept map can be used in many ways, from gathering information to solving problems. It is composed of nodes and links that show the relationship of one concept to another. A sample concept map follows:

Quadrant 3 focuses on brainstorming strategies based on the previous quadrants. Context and experience are important elements to be used in identifying possible solutions to implement strategies. Challenges that may surface also must be identified and included in the discussion to generate appropriate strategies. At this stage, participants should suggest and build on several ideas. Criticism should be withheld unless it is conveyed in a positive manner. Before concluding this session, participants must prioritize the list of strategies according to a set of criteria identified during the plenary.

The fourth Quadrant requires that an action plan be drafted based on the set of strategies, key lessons, and insights identified in the previous quadrants. An action plan must contain the following information:

- Strategies or courses of action

- Persons or institutions responsible for carrying out the activities

- Timeframe for the planned activities

- Resources (financial and human) needed to carry out the activities

Any comments? Please notify us here.