Lead authors: Renzo Lavin & Carolina Cornejo (ACIJ)

Contributing authors: Sruti Bandyopadhyay (World Bank)

- Module 01

- Understanding Each Other Better

- An Approach to SAI's

AUDIT 101: SAIs’ mission, structure, mandate, and various models

SAIs´ models and characteristics

SAIs may fall into one of three broad organizational categories, depending on the institutional set-up and accountability system within a given country context: the Westminster model; the Board, or Collegiate model; and the Court, or Judicial model (also called the Napoleonic model). Each model displays distinctive features in the scope of audit tasks, the SAI´s enforcement authority, and its relationships with the legislature. Table 1 lists the main characteristics of each SAI model.

|

SAI Model |

Westminster |

Board/Collegiate |

Court/Judicial |

|

Head |

Auditor General (AG) or Comptroller General (CG) |

President |

President/First President |

|

Organizational structure |

Monocratic General Audit Office or Comptrollers´ General

|

Collegiate

|

Collegiate Court of Auditors or Tribunals of Accounts

|

|

Accountability system |

Parliamentary

|

Parliamentary

|

Judicial

|

|

Relations with parliament |

|

|

|

|

Types of audit |

|

|

|

|

Reporting |

|

|

|

|

Strengths |

|

|

|

|

Weaknesses |

|

|

|

|

Examples |

|

|

|

Source: DFID 2004.

Source: DFID 2004.

To whom are SAls accountable?

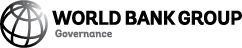

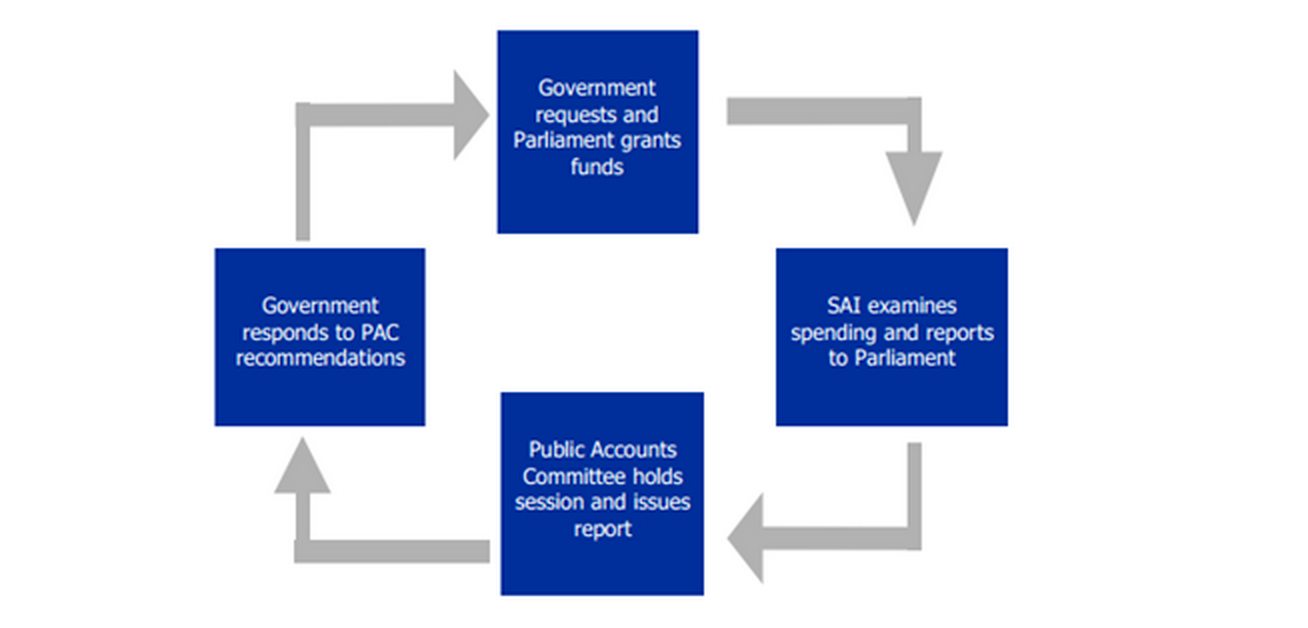

We must note that each model of SAI reports to a different branch of power. Then the question to be addressed is, how does the overall model influence accountability by the SAI and the feasibility of citizen engagement? With SAls that follow a Westminster or Board model (hence reporting to parliament), citizen engagement within the accountability system often is channeled through public accounts committees (or other responsible parliamentary committees).

Although SAls' direct engagement with citizens might at first be regarded an infringement of their accountability to parliament, accountability to external stakeholders is mandatory (given SAls' role within the democratic system), as well as complementary to SAI answerability to congress. That broader engagement can indeed contribute to institutional strengthening and to overcoming several challenges mentioned before.

Given that SAls are auxiliary to the legislature, such a relationship may frame the scope of citizen engagement (for example, SAls would most probably not provide citizens with information that has not been reported to parliament). For instance, the General Audit Office in Argentina decided to a.mnce transparency and citizen engagement by publishing all audit reports immediately after they were sent to the parliamentary committee. In fact, that decision was directly linked to (a) the lack of timely follow-up of audit reports by parliament, and (b) the perceived need to be accountable to the citizenry and advocate for strengthened accountability by engaging civil society.

Similarly, with the Court model—in which SAls may report to parliament or to the head of state, although they most commonly operate independently of the executive and legislative branches—citizen engagement may be framed following a different approach, given the judicial nature of the audit process, as well as the enforcement capabilities of SAI observations. Because audit is highly technical within this system, direct engagement with citizens may be more difficult to incorporate in the audit process itself, but it may prove effective at the follow-up stage, especially to monitor budget execution and to help identify budget priority areas.

2015 Copyright - World Bank Institute & ACIJ

TPA Initiative – ACIJ (2011): “Diagnostic Report on Transparency, Citizen Participation and Accountability in Supreme Audit Institutions of Latin America”

TPA Initiative – ACIJ (2013): “Audit Institutions in Latin America. Transparency, Citizen Participation and Accountability Indicators”.

Cornejo, C., Guillan, A. & Lavin, R. (2013): “When Supreme Audit Institutions engage with civil society: Exploring lessons from the Latin American Transparency Participation and Accountability Initiative”, U4 Practice Insight Nº5, Bergen, U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre - Chr. Michelsen Institute.

O´Donnell, Guillermo (2001): “Horizontal. Accountability: The legal institutionalization of mistrust”, Buenos Aires, PostdataN°6, pp. 11-34.

OECD (2013): “Citizen Engagement and Supreme Audit Institutions” (Stocktaking Report: DRAFT).

UN (2013): “Citizen Engagement Practicesby Supreme Audit Institutions”, Compendium of Innovative Practices of Citizen Engagementby Supreme Audit Institutions for Public Accountability.

INTOSAI (2013): “The Value and Benefits of Supreme Audit Institutions – making a difference to the lives of citizens”,ISSAI 12.

INTOSAI (2013): “Beijing Declaration”.

OLACEFS (2013): “The Santiago Declaration”.

INTOSAI (2010):“Principles of transparency and accountability”,ISSAI 20.

INTOSAI (2010):“Principles of Transparency and Accountability - Principles and Good Practices”, ISSAI 21.

INTOSAI (2007): “The Mexico Declaration on SAI Independence“, ISSAI 10.

OLACEFS (2009): “Asuncion Declaration”.

INTOSAI (1977): “Lima Declaration”.

UN (2011): Resolution A/66/209 “Promoting the efficiency, accountability, effectiveness and transparency of public administration bystrengthening supreme audit institutions”.

UN (2003): “United Nations Convention against Corruption”.