Lead authors: Renzo Lavin & Carolina Cornejo (ACIJ)

Contributing authors: Sruti Bandyopadhyay (World Bank)

- Module 01

- Understanding Each Other Better

- An Approach to SAI's

AUDIT 102: The audit process

The audit process

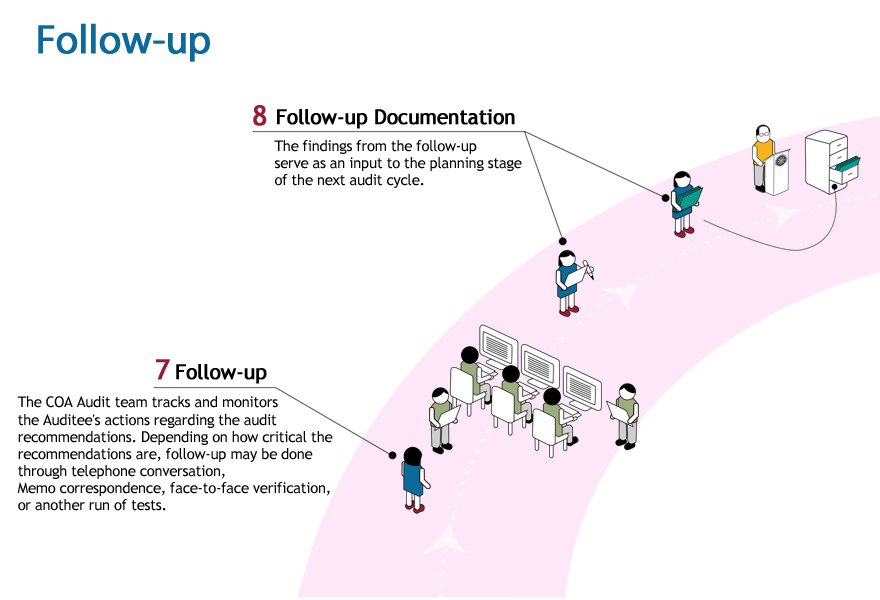

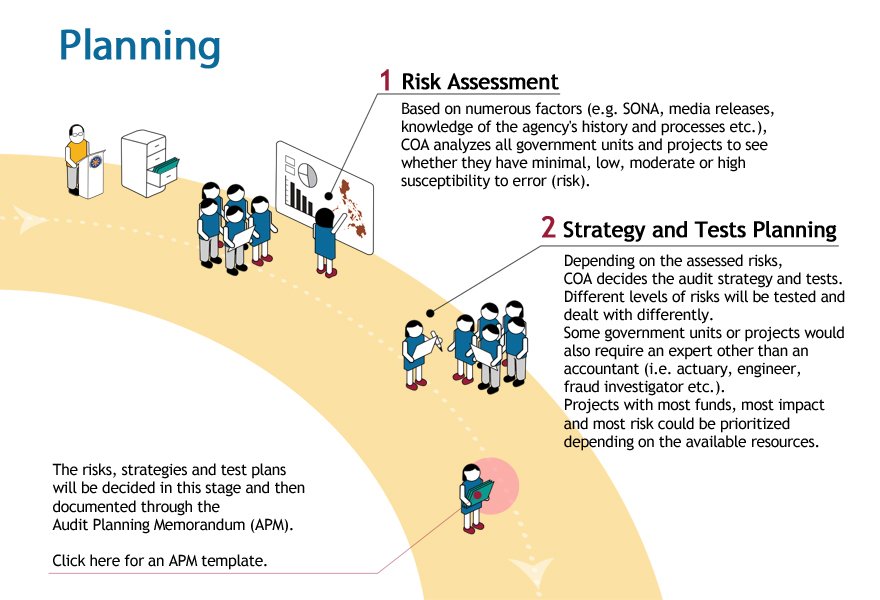

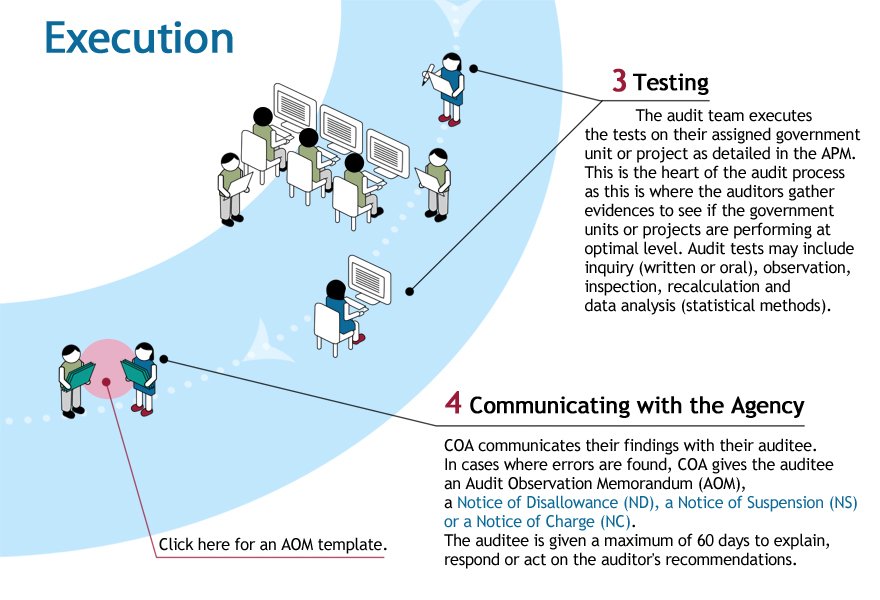

The audit process can be classified in four different phases: 1. audit planning; 2. execution (field work, evidence gathering, and drafting of the report); 3. reporting and dissemination (submission of the report to the authorities and dissemination); and 4. follow-up (monitoring of the auditee’s actions).

Citizen collaboration can take place in each phase of the audit cycle:

For further information on citizen engagement mechanisms and good practices worldwide, go to Module 3.

Planning:

In Oman 1, citizens can provide valuable input to audit planning through the SFAAI Smart Phone Apps, an online system the State Financial and Administrative Audit Institution launched in 2011 to receive complaints and reports that could help detect financial and administrative deviations in public sector companies. That feedback mechanism has achieved impressive results during the first two years in practice, as citizens have reported more than 600 financial violations and complaints regarding misuse of power and improper bids, among others.

Execution:

In India2, social audits are supported by the SAI in an attempt to engage credible citizens’ groups whose members have expertise in specific areas. Through active media coverage of forthcoming audit exercises, the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) invites those groups to share suggestions and information regarding the subject matter. This activity has expanded the CAG´s outreach and allowed auditors to get deeper insight into the auditees’ business, thereby leading to better-rounded audit reports.

Reporting and dissemination:

In Montenegro3, the State Audit Institution summarizes key findings and recommendations of individual audit reports in its annual report of audit reports. That summary reports which laws were violated most often, along with an explicit account of how many and which of its recommendations from the previous year were implemented. The dissemination of this kind of information, together with individual audit reports, is critical to ensuring that corrective actions are undertaken. For instance, the Institut Alternativa, a local research CSO, has begun to monitor SAI’s effectiveness by checking to see if the audit entities comply with deadlines and reporting back to the SAI about what has been done to address the recommendations. Support from civil society can stir up attention about specific aspects of SAI work, get media coverage, and contribute to exerting pressure on auditees so that they address the irregularities detected in audit exercises.

Follow-up:

In South Africa4, audit reports are published and thoroughly disseminated. Using the audit findings, the Public Service Accountability Monitor (PSAM)—a research and advocacy organization—works closely with the national legislature to track government agency responses to instances of financial misconduct and corruption identified by the Auditor General so as to pressure governments to take corrective action. PSAM publicizes audit findings in press releases and on radio talk shows, publishes a scorecard measuring the comparative compliance of various provincial agencies with public finance law, and organizes public campaigns highlighting the large number of audit disclaimers issued by provincial audit entities, all of which has led to stronger financial management practices in provincial government agencies.

Practical example: the audit process at Philippine’s Commission on Audit

Who are the relevant actors during the audit process, and what are their roles?

Practical examples and additional information

- The auditor: SAI organization chart (US GAO - Norway)

- The audittees: i-kwenta, SAI Argentina

- The parliament: Article INTOSAI “Relations Between SAIs and Parliamentary Committees”, 2003

Stakeholders in the PFMA system (DFID, 2005)

2015 Copyright - World Bank Institute & ACIJ

TPA Initiative – ACIJ (2011): “Diagnostic Report on Transparency, Citizen Participation and Accountability in Supreme Audit Institutions of Latin America”

TPA Initiative – ACIJ (2013): “Audit Institutions in Latin America. Transparency, Citizen Participation and Accountability Indicators”.

Cornejo, C., Guillan, A. & Lavin, R. (2013): “When Supreme Audit Institutions engage with civil society: Exploring lessons from the Latin American Transparency Participation and Accountability Initiative”, U4 Practice Insight Nº5, Bergen, U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre - Chr. Michelsen Institute.

O´Donnell, Guillermo (2001): “Horizontal. Accountability: The legal institutionalization of mistrust”, Buenos Aires, PostdataN°6, pp. 11-34.

OECD (2013): “Citizen Engagement and Supreme Audit Institutions” (Stocktaking Report: DRAFT).

UN (2013): “Citizen Engagement Practicesby Supreme Audit Institutions”, Compendium of Innovative Practices of Citizen Engagementby Supreme Audit Institutions for Public Accountability.

INTOSAI (2013): “The Value and Benefits of Supreme Audit Institutions – making a difference to the lives of citizens”,ISSAI 12.

INTOSAI (2013): “Beijing Declaration”.

OLACEFS (2013): “The Santiago Declaration”.

INTOSAI (2010):“Principles of transparency and accountability”,ISSAI 20.

INTOSAI (2010):“Principles of Transparency and Accountability - Principles and Good Practices”, ISSAI 21.

INTOSAI (2007): “The Mexico Declaration on SAI Independence“, ISSAI 10.

OLACEFS (2009): “Asuncion Declaration”.

INTOSAI (1977): “Lima Declaration”.

UN (2011): Resolution A/66/209 “Promoting the efficiency, accountability, effectiveness and transparency of public administration bystrengthening supreme audit institutions”.

UN (2003): “United Nations Convention against Corruption”.